It’s that time of year again—school is winding down, final exams are being talked about, and the countdown to summer break has officially begun. For students, the promise of freedom, lazy mornings, and beach days feels almost within reach. Yet, just as we begin to dream of bonfires and late-night ice cream runs, we are disrupted by the looming thoughts of school continuing through the summer: the inevitable arrival of summer assignments, and most notoriously, the dreaded summer reading.

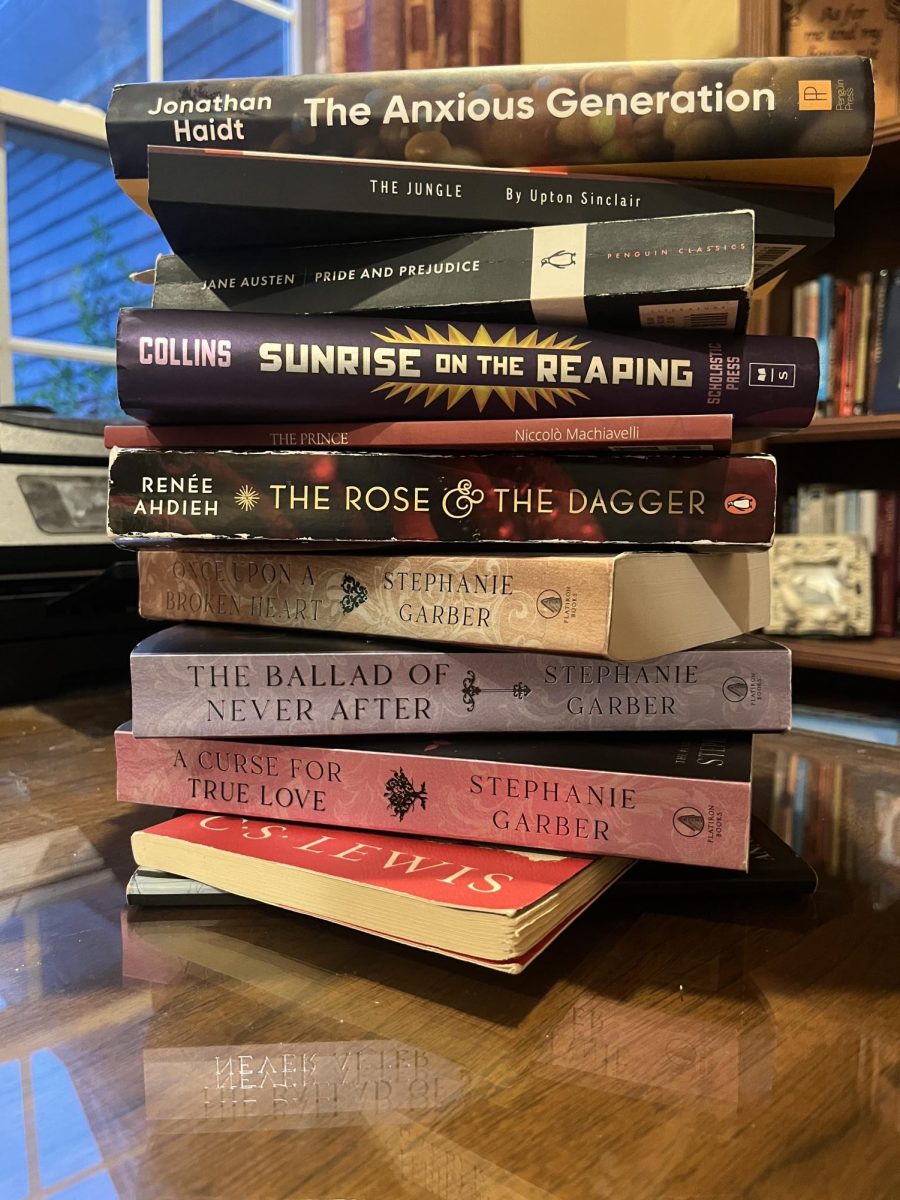

Now, I am not someone who dislikes books. In fact, I love them. From the timeless classics of Jane Austen and Franz Kafka, to the gripping modern tales of Suzanne Collins and Stephanie Garber, I have always appreciated the power of a good story. But somehow, the magic disappears when the book is stamped with the label “summer reading.” It’s as if the moment a book becomes an assignment, it stops being a story and becomes a box to check off for next year’s learning. Maybe it’s the pressure of a quiz on the first day back, or the soul-draining guided reading questions that turn plot into paperwork. Either way, the experience shifts from pleasure to pressure.

And I am not alone in feeling this way.

Ludlow High School, unlike some other schools that are slowly phasing out mandatory summer reading, still assigns books over break. The idea behind summer reading is a fair one—keep students’ minds sharp, encourage literacy, and prepare them for upcoming class work. But in practice, it does not always achieve these goals.

Junior Ben Goodreau says, “Rarely [do] I choose to read [on] my own time. Summer reading … allows me to stay fresh on vocab for my three-month vacation. But for the kids that do read, summer reading serves no purpose because they would read … anyways, and for the kids that do not, it creates resentment towards reading.”

In other words, summer reading only works in theory, or for a very specific group of students. It attempts a one-size-fits-all solution for a very diverse student body (especially since the books assigned are very one-size-fits-all, but that is a different topic for a different day)

In other words, summer reading only works in theory, or for a very specific group of students. It attempts a one-size-fits-all solution for a very diverse student body (especially since the books assigned are very one-size-fits-all, but that is a different topic for a different day)

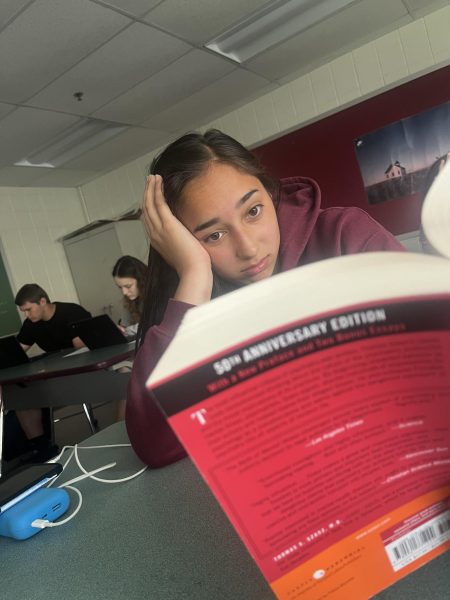

Personally, I found the book I had assigned to me this summer, The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt, to be fascinating. It offered a compelling exploration of how social media has shaped Generation Z and sparked meaningful reflections. But even with my interest in the topic, completing the assignment was a grind. I had to follow a strict reading schedule—60 pages a day—to finish the 400-page book before leaving for a beach vacation, where I preferred to read books unattached from school’s assignments. That rushed pace gave me headaches, both literal and figurative, and turned an otherwise enjoyable book into a task.

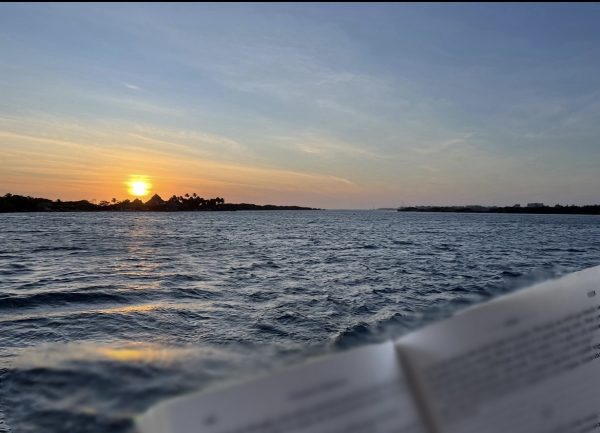

Ironically, once the pressure was off, I read two more books on vacation—one 328 pages, the other 127—with ease and enjoyment. There were no reading guides or impending deadlines, just me and the stories. This difference speaks volumes. The issue isn’t that students dislike reading—it’s that they dislike how reading is forced upon them during the summer.

When I asked around, I found that many students echoed the same frustrations. Amanda Miller, a fellow student, put it simply: “I have always liked reading, but the only assignments I have liked were when I got to pick a book, not be assigned one.” Her experience mirrors mine—and likely many others. The rare joy in summer reading comes when students are allowed to choose from a list or pick a book that aligns with their interests. That small bit of independence can be the difference between resentment and engagement.

What’s more, the focus on English classes alone feels inconsistent. Math teacher Mr. Martin offered an insightful perspective: he does not assign summer homework to maintain students’ math skills. Instead, like most other subjects, he uses the first weeks of the new school year to review past material. If this strategy works for math, science, history, and other curricula, why is English the exception? Either all subjects should have summer work, or none should.

Classmate Zoe Velevitch also offered a balanced view: “I think summer reading can be beneficial under certain circumstances.” And she’s right. When thoughtfully designed—with room for choice, flexibility, and relevance—summer reading has the potential to inspire rather than stifle.

Instead of mandatory reading with rigid rules, schools like Ludlow should consider alternatives that actually build enthusiasm and foster lifelong reading habits. Imagine a summer reading program where students could choose a book from a wide range of genres, write a short reflection, or even share their thoughts in a creative format—like a podcast, a blog post, or a video review. Schools could also partner with local libraries to create reading challenges that include incentives, book clubs, and community discussions. These approaches would not only make reading more enjoyable but also more meaningful.

In the end, summer reading is not inherently a bad idea—it’s just often executed in ways that miss the mark. When reading becomes a chore rather than a choice, even the most book-loving students can lose interest. But it does not have to be that way. By reimagining summer reading as a flexible, student-centered opportunity—one that prioritizes curiosity, creativity, and genuine engagement—schools can transform it into something students actually look forward to. After all, the ultimate goal of education is not just to assign work, but to inspire lifelong learning. And summer, with all its freedom and possibility, is the perfect place to start.

maddie • May 30, 2025 at 12:34 pm

wow, love this!